Atoms are made up of two main parts: the nuclei, where the protons and neutrons are found, and the orbitals, where you can find the tiny electrons. But something you might not know is that these electrons are not just placed anywhere, they have quirks and preferences that are very similar to the ones we humans have when we choose where to sit on a bus.

The orbitals and the bus floors

Imagine you live in London, an iconic city whose symbol includes those red double-decker buses. You wait at your stop and, when the bus arrives, you see it is empty and you can choose any seat you like.

Which seat would you choose?

If you were just a tourist in London, I am sure you would choose the top deck; like an excited kid you would go upstairs and enjoy the city views. But if you are a regular who takes this bus every day of the week, you will most likely stay on the lower deck. What a drag to climb such a narrow staircase…!

It is much easier and more comfortable to stay on the lower deck. And this is exactly what electrons do: they fill the different floors depending on how much effort it takes for them to be on each one.

Electrons and laziness

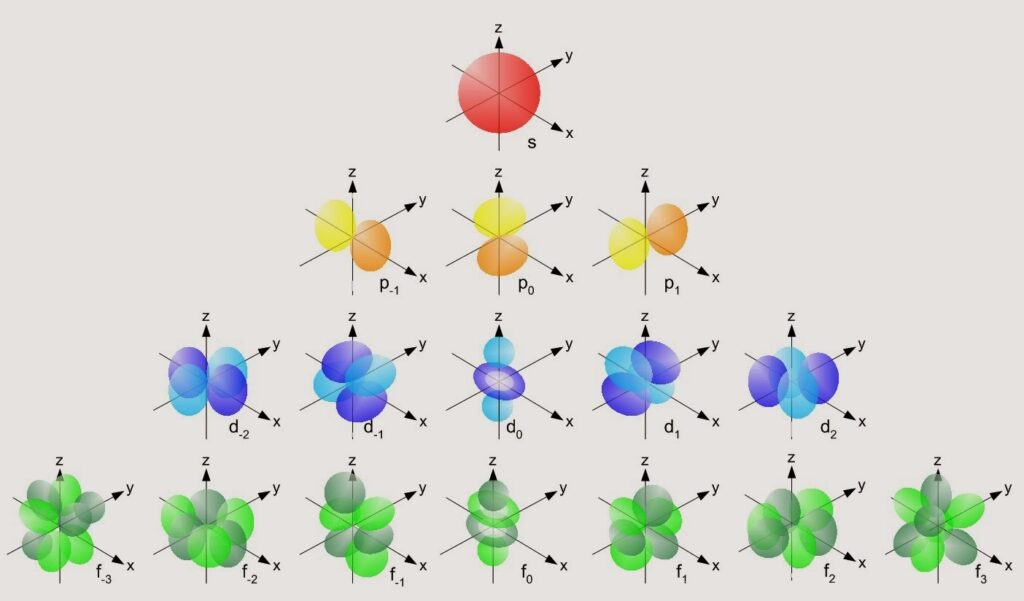

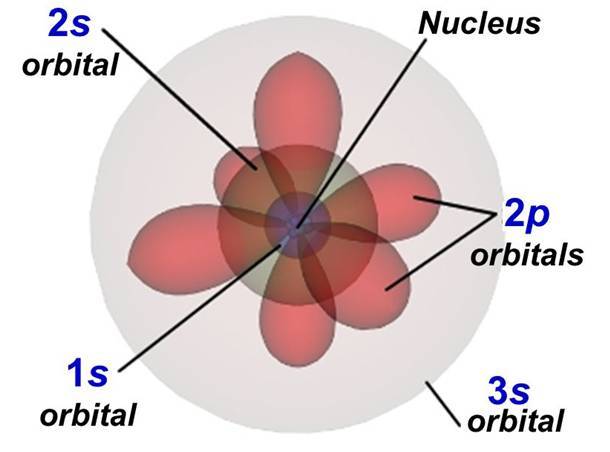

The bus floors are the different atomic orbitals, the regions where electrons can be. First the orbitals that require the least effort for the electron will be filled, the orbitals with the lowest energy, just like the regular bus passengers. But what is it that makes each floor have one energy or another?

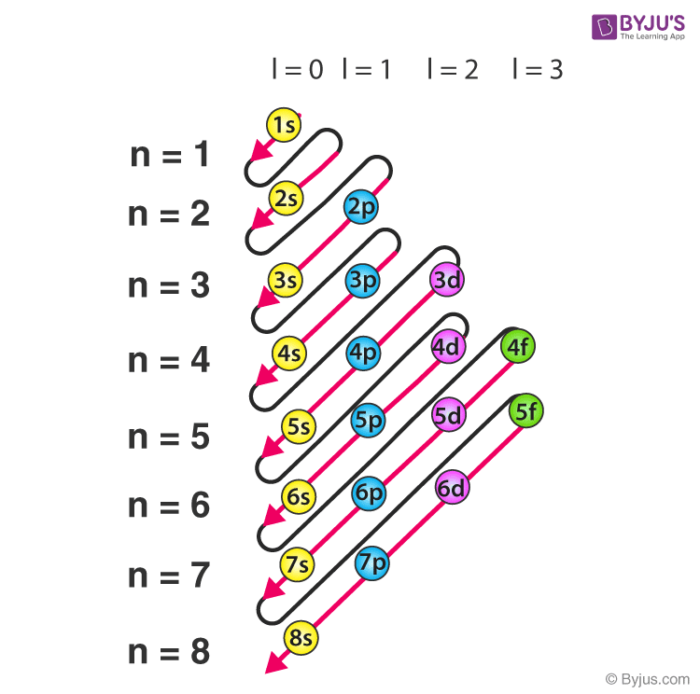

- The distance to the atom’s nucleus, or how high the floor is. The lower the floor, the less energy it adds to the total. For example, the first floor (n=1) has less energy than the second (n=2) for this reason. Each floor has a name assigned to it: s (n=1), p (n=2), d (n=3), f (n=4), g (n=5).

- The shape of the orbital, or the number of seats on that floor. In atoms, the shape of the orbital determines how much rotational energy the electron has, since it defines how it will move. The more pairs of seats available on the floor, the bigger it has to be, and therefore the “lazier” we feel about having to look for a spot on it.

So, the energy of each floor can be compared by adding up the number of seat pairs on the floor and how high that floor is. One orbital will have more energy than another if its (n+l) is larger than that of another orbital.

Source: elfisicoloco.blogspot.com

The seats and Hund’s rule

Once you are on the floor that suits you best, you reach what might be the tensest moment of the whole process: choosing a seat.

The first passenger to get on will not have much trouble choosing and will probably take the closest seat. Things get interesting when the next passengers of the atomic bus arrive: the new passengers who get on the bus will sit in pairs of seats for 2 that are still empty, avoiding bothering the passengers who are already seated and making themselves as comfortable as they can.

And electrons do exactly the same!

This “quirk” electrons have of avoiding each other is known as Hund’s Rule, and it allows them to experience less electric influence from the rest of the electrons in the atom, by being nicely spread out among the different orbitals (or pairs of seats) on the same floor.

But… what happens when all the pairs of seats already have a passenger?

A bus with ALSA seat upholstery filling up with people represented by arrows

Comfort and the Pauli exclusion principle

The poor electrons, just like the bus passengers, eventually have no choice but to share a seat with someone else. But there is a very important detail: they cannot sit in the same way as the electron that is already in the orbital or, in our analogy, as the passenger who is already seated. This happens because of the Pauli exclusion principle, which does not allow two electrons to be in the same quantum state.

In simple terms, the two electrons cannot have the same properties and be in the same place at the same time. They cannot be identical in the same spot and, since they are in the same pair of seats, one of their properties has to be different from that of the electron that is already sitting there.

‘Spin’ and getting comfortable

The same ALSA-upholstered bus filling up with the last passengers getting on.

And the property that changes so more electrons can fit is the ‘spin’. Spin is a very complex quantum property that represents the intrinsic rotation of the electron. It is something like the rotational energy it has by itself, without any external influence. We will talk more about spin another time, but the important thing here is that it has to be different for electrons in the same orbital.

So the electrons that arrive first at the orbital sit with their spin “up” (an arrow pointing upwards), nice and comfy, while the second one has no choice but to take its place with spin “down” (an arrow pointing downwards), more squeezed in and with less room.

The same thing happens with our passengers: the first one makes themselves very comfortable, so the second one cannot spread out as much and has to squeeze in more. The electrons keep filling the orbital they are in until it is completely full, until there are no more free seats left on that floor. And if there are none left, they move on to the next one, following exactly the same rules.

An example with a real element

Now that you understand how electrons arrange themselves inside the atom, you are probably curious to see a real example. Let us use oxygen, which has 8 protons in its nucleus and 8 electrons in its orbitals.

The first electrons stay on the first “floor”, the 1s orbital. One sits with spin up and the other with spin down. On the second “floor”, the 2s orbital, exactly the same thing happens because there are the same number of seats. That already accounts for 4 of the 8 electrons.

So the remaining 4 go up to the last floor, the 2p orbital. The electrons spread out, nice and comfortable, with spin up, filling one seat of each pair. When the last one arrives, it has no choice but to sit next to another electron and take spin down. All the electrons in oxygen have settled into the arrangement that gives the most stability to the atom or, in other words, they have found the lowest-energy configuration.